The History Of How We Live Today

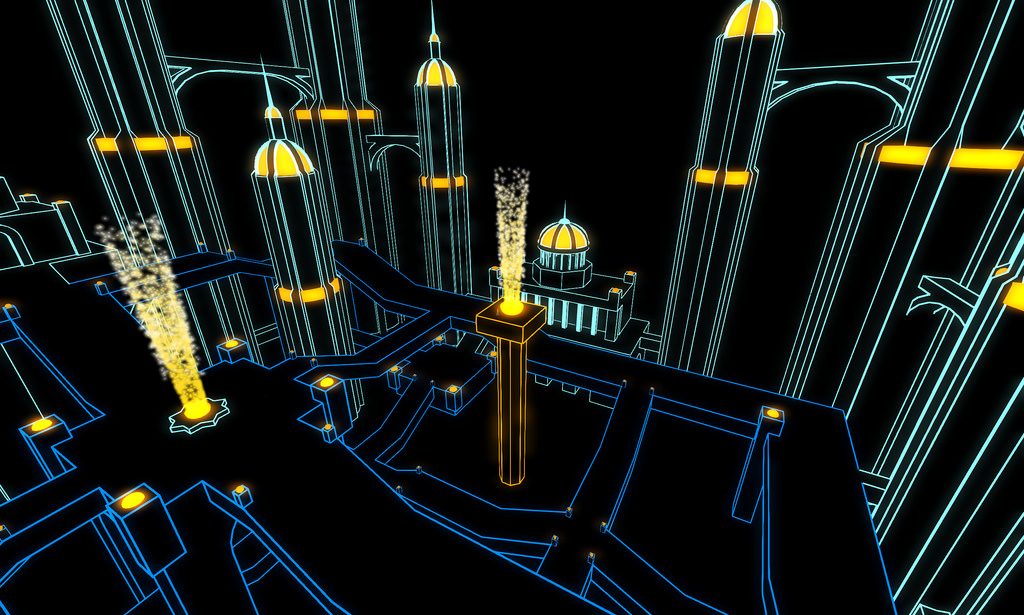

The Future

While the cult of the star architect has soared over the decades and property developers have displaced bankers as the new super-rich, the figure of the local town planner has become comic shorthand for a certain kind of faceless, under-whelming dullard.

While the cult of the star architect has soared over the decades and property developers have displaced bankers as the new super-rich, the figure of the local town planner has become comic shorthand for a certain kind of faceless, under-whelming dullard.

Sir Peter Hall – 2014

As the positive elements of foreign investment and private capital in our cities increase, drawing people in, the issue of the housing deficit becomes more apparent.

Since 2000, the UK population has grown at a pace of 0.6% per year – the fastest period of population growth since the 1960s when the new town movement was in full swing. We have once again reached that tipping point where drastic action is required to rebalance the supply of housing vs. demand in the UK.

Despite the clear need for quality housing, an issue which is time and time again voiced by local housing associations, environmental issues and the loss of green spaces are at odds with further development.

The need for good local planners to make sense of the issues at hand, in order to devise a plan to satisfy all needs, by creating healthy and comfortable green communities, is more essential than ever.

However, the days of the star town planners such as Le Corbusier, Parker and Unwin are well and truly over. Town planners are today seen as interfering jobsworths, civil servants who, more often than not, are more interested in hindering housing developments than being the driving force behind them.

The British government, constantly under fire to answer the question of the housing deficit, and who would benefit greatly from imaginative and pro-active local planning departments, are  perhaps their biggest opponent. In 2012, David Cameron, eager to address the housing question, promised that his government was “determined to cut through the bureaucracy that holds us back – and that starts with getting the planners off our backs”

perhaps their biggest opponent. In 2012, David Cameron, eager to address the housing question, promised that his government was “determined to cut through the bureaucracy that holds us back – and that starts with getting the planners off our backs”

It is, however, unsurprising that planning departments lack the spark which was so prevalent in the past; it is no longer a necessity for planners to have the slightest grasp of the creative and architectural aspects of the planning process, only the rules and regulations which must be adhered to. The problem appears to stem from the point of education, those talented individuals who have an interest in architecture, creativity and regeneration, who want to discuss the issues of town planning, do not want to become town planners. Planning courses teach only the procedural and legal elements of the process, whereas a course in Urban Studies and Cultural Studies would satisfy those who are actually desperately needed in the profession of Town Planning.

The solution appears to be an overhaul of the notion of the town planner, to reinvigorate the profession with an injection of young talent. Just as the youthful team responsible for Milton Keynes were able to create a community unlike anything which had been attempted prior, a new generation of eager and creative Town Planners may be the answer to the housing enigma.

The age old question remains; should we overhaul existing towns and cities to accommodate the growing population or invest in new communities. Some argue that the concept of New Towns and Garden Cities is fundamentally flawed. The Future Spaces Foundation has researched this very question and claims that 67 Garden Cities, each with populations of 30,000, would be required to satisfy housing requirements. To put this in perspective, the land required would amount to 675km² plus additional land to construct new roads and rail links. It is argued that this is an absurd undertaking and a far more plausible solution, from both logistic and economical perspectives, would be to allow existing communities to absorb the surplus population through regeneration.

The age old question remains; should we overhaul existing towns and cities to accommodate the growing population or invest in new communities. Some argue that the concept of New Towns and Garden Cities is fundamentally flawed. The Future Spaces Foundation has researched this very question and claims that 67 Garden Cities, each with populations of 30,000, would be required to satisfy housing requirements. To put this in perspective, the land required would amount to 675km² plus additional land to construct new roads and rail links. It is argued that this is an absurd undertaking and a far more plausible solution, from both logistic and economical perspectives, would be to allow existing communities to absorb the surplus population through regeneration.

The government have introduced a number of initiatives including: Reducing restrictions on new housing projects, an investment of £474 million in local infrastructure, a £500 million ‘Get Britain Building’ fund for developers and a plan to bring Britain’s 635,000 empty houses back in to use. These initiatives, although admirable and display a desire to address the housing deficit, lack the clarity and cohesion of the post-war New Towns plan.

Fundamentally, the issue comes down to economics. Housing developers are commercial outfits, if demand outweighs supply, the price of their product, i.e. homes, will remain high, if the market is saturated, prices fall. The emphasis is not on creating new communities of which Britain can be proud, but achieving the largest profit margin. The government is eager for developers to create good value homes for working class families, whereas developers are happy to drip feed the middle classes, keeping demand and prices high.

However, one development offers hope for the future, it is a government led operation and is reminiscent of the golden age of town planning. Announced by the Coalition Government in March 2014, the new town is called Ebbsfleet Garden City, the project is backed by £200 million of government funding and has planning permission for 15,000 new homes. The Ebbsfleet, Northfleet and Swanscombe area is in North Kent, it is 15 minutes from London by high speed rail link, has a Eurostar terminal and is a short distance from the vast Bluewater shopping centre. Both Redrow and Barratt have committed to delivering a combined 1,100 homes, 15% of the Redrow development being social housing. Additionally, the first new theme park in Britain for decades, ‘Paramount London’, may be built within the designated area, providing jobs and tourism.

A second neo-Garden City has been announced in Bicester, Oxfordshire, furthermore, a third project is in the pipeline but has yet to be named.

The Ebbsfleet Garden City project is not only an opportunity to create an exciting, new community, it is a beacon which will excite, invigorate and entice those creative minds which are so urgently needed. We may be entering a brand new golden era of New Towns and Garden Cities, our future is in the hands of the next generation of town planners. Will they have what it takes to live up to the precedent set by the luminaries of the past? Only time will tell.

Sir Peter Hall

Town planners have become a hindrance to new projects.

Sat empty - Could the need for more homes be absorbed by existing communities?

From model (left), to reality (above), Ebbsfleet Garden City is on of Britian's largest housing developments.

© 2021, D A Phipps, All Rights Reserved