The History Of How We Live Today

Garden Cities

A Garden City is a town designed for industry and healthy living; of a size that makes possible a full measure of social life, but not larger; surrounded by a permanent belt of rural land; the whole of the land being in public ownership or held in trust for the community. C.B. Purdom, 1919

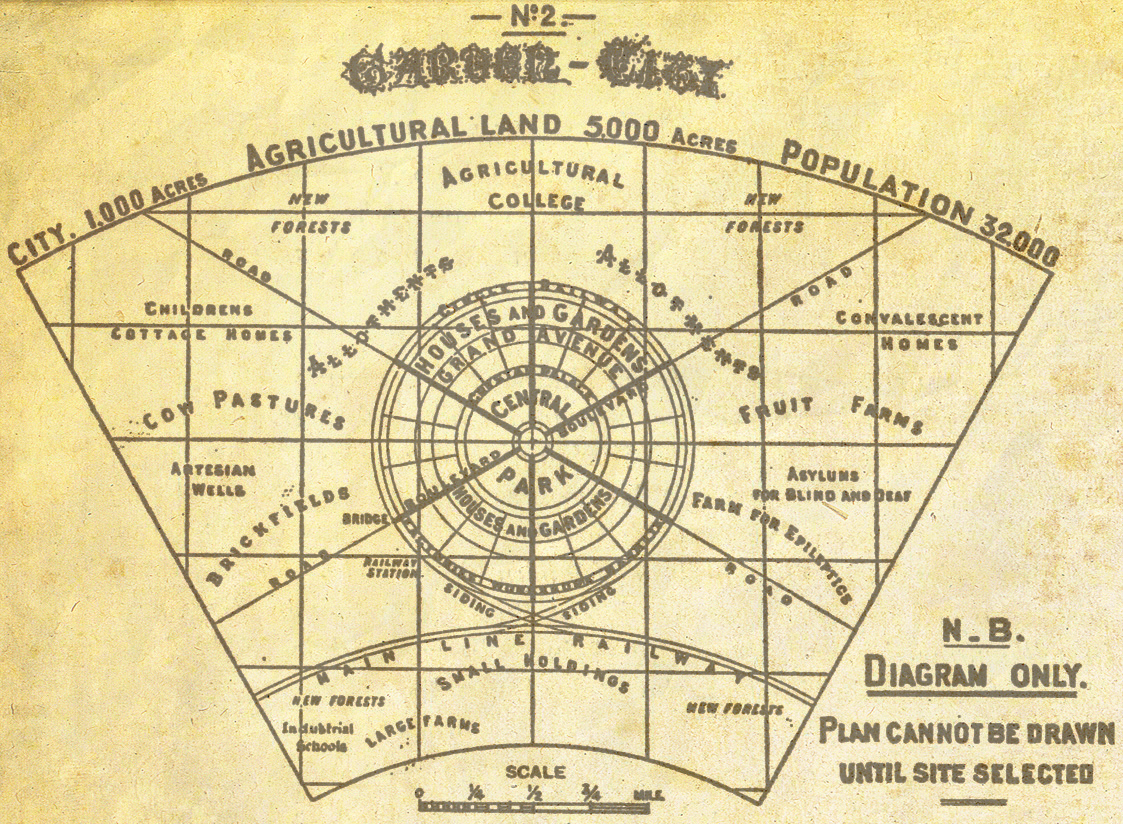

In 1898 an unknown Court Reporter named Ebenezer Howard publishes a book entitled: ‘To-morrow – A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’. The book sets out Howard’s vision for what he sees as the answer to overcrowded cities and the lack of affordable good housing for the working class. Howard not only has a plan for how towns are designed but also where they are located. Existing cities should be encircled by a band of greenbelt, a vast area of countryside which cannot be built on, so as to contain urban sprawl and protect the beauty of rural regions. Beyond the greenbelt should be satellite towns of limited size, surrounded by their own green belt, which Howard describes as Garden Cities. Garden Cities

In 1898 an unknown Court Reporter named Ebenezer Howard publishes a book entitled: ‘To-morrow – A Peaceful Path to Real Reform’. The book sets out Howard’s vision for what he sees as the answer to overcrowded cities and the lack of affordable good housing for the working class. Howard not only has a plan for how towns are designed but also where they are located. Existing cities should be encircled by a band of greenbelt, a vast area of countryside which cannot be built on, so as to contain urban sprawl and protect the beauty of rural regions. Beyond the greenbelt should be satellite towns of limited size, surrounded by their own green belt, which Howard describes as Garden Cities. Garden Cities  should provide beautiful and imaginatively designed housing for all, regardless of class and social standing. Howard also specifies that districts should be of mixed class, i.e. large houses adjacent to small cottages. He puts emphasis on the benefits of outdoor recreation and leisure activities, since he believes this is key to health and well-being, in addition; provision should be made for residents to have access to allotments in order to grow their own fruit and vegetables. Howard also specifies that jobs should be provided by local industry within the town and be within easy commuting distance. Howard offers a vision of towns free of slums, which enjoy the benefits of both town (such as opportunity, amusement and good wages) and country (such as beauty, fresh air and low rents). In order to invigorate community spirit and provide funds for upkeep, Howard specifies that the natural increase in value of the land should return to the community.

should provide beautiful and imaginatively designed housing for all, regardless of class and social standing. Howard also specifies that districts should be of mixed class, i.e. large houses adjacent to small cottages. He puts emphasis on the benefits of outdoor recreation and leisure activities, since he believes this is key to health and well-being, in addition; provision should be made for residents to have access to allotments in order to grow their own fruit and vegetables. Howard also specifies that jobs should be provided by local industry within the town and be within easy commuting distance. Howard offers a vision of towns free of slums, which enjoy the benefits of both town (such as opportunity, amusement and good wages) and country (such as beauty, fresh air and low rents). In order to invigorate community spirit and provide funds for upkeep, Howard specifies that the natural increase in value of the land should return to the community.

Ebenezer Howard

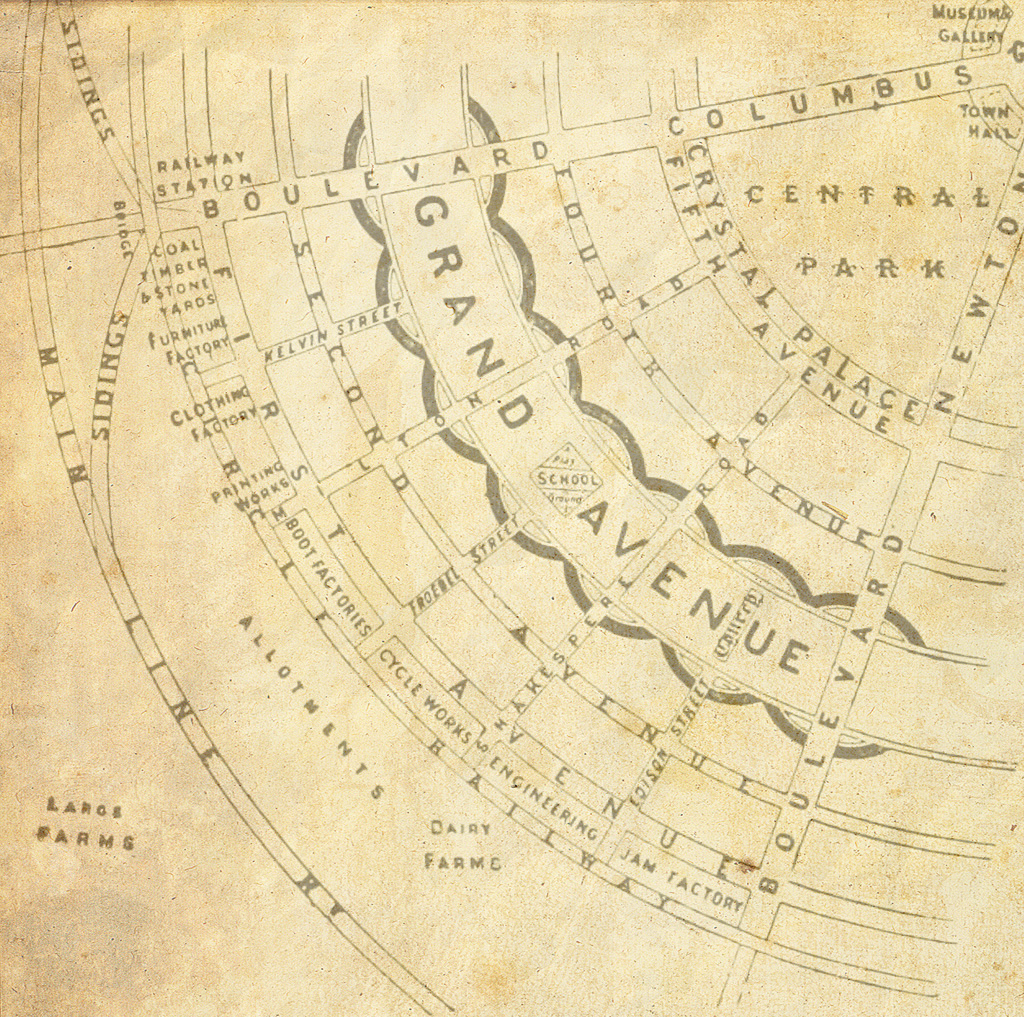

Diagrams from 'To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform

Howard is an unlikely revolutionary; his radical ideas have been created and nurtured by a combination of events both in his personal life as well as those which have had a nationwide influence.

He has no particular advantages of class, or special education, but at an early age he is sent away to school, where he is exposed to a more rural environment. Howards schooling takes place in Suffolk, then Cheshunt in Hertfordshire and at Stoke Hall, Ipswich. He works in a series of clerical posts and learns shorthand. Howard transcribes sermons for one of his early employers, Dr Parker of the City Temple, who observes that he could be a successful preacher.

Howard, influenced by an Uncle who is a farmer, emigrates to the United States at the age of 21 with the intention of farming. He travels west and settles on 160 acres in Howard County, Nebraska as a homestead farmer. This venture proves unsuccessful. Howard then makes his way to the city of Chicago to resume his career as an office worker. He arrives at a time when the city is recovering from the great fire of 1871 which destroys most of the central business district. Howard witnesses the regeneration of the city and the development of the rapidly growing suburbs. The American landscape architect, F.L.Olmsted, the creator of New York’s Central Park, prepares a master plan for a suburban community with an informal layout and spacious  plots for houses with landscaped parkway roads. Observing the planned renaissance of the area proves highly influential to the young Howard. Interestingly, at the time of Howard’s visit, Chicago is known as The Garden City.

plots for houses with landscaped parkway roads. Observing the planned renaissance of the area proves highly influential to the young Howard. Interestingly, at the time of Howard’s visit, Chicago is known as The Garden City.

In 1876 Howard returns to England where he joins a firm of official Parliamentary reporters. Here he becomes aware of and frustrated by how difficult Parliament finds it to create solutions to the problems of housing and labour. Howard observes that one issue alone proves to be the biggest hindrance to progress, the continued stream of migration from rural districts to the already overcrowded cities.

Industrialisation is responsible for attracting the population into the cities with the promise of better wages, more opportunities for work and exciting social activities. The decimated agricultural communities see their able bodied population dwindle, depressing the economy of these areas and leaving villages deserted with the remaining population crammed into poor quality dwellings. This, in turn, increases the pressure that drives the people towards towns and cities.

Cities become horrendously overcrowded, inadequate housing, substandard water supplies, inferior drainage and unfit sewerage systems are prevalent; however, rents and prices remain high. Unsanitary conditions lead to disease; several outbreaks of cholera between 1831 and 1854 kill hundreds of thousands, creating national concern for public health. The repugnant conditions are confirmed by reports around the early 1840's which give an account of ‘Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Classes’. It is confirmed that polluted water supplies due to inadequate or total lack of sanitary sewage and waste facilities, poor burial practices, and the effect of overcrowded housing are all sources of disease.

F.L.Olmsted's Plan for Central Park, New York.

“Wretched houses with broken windows patched with rags and paper; every room let out to a different family, and in many instances to two or even three – fruit and ‘sweetstuff’ manufacturers in the cellars, barbers and red-herring vendors in the front parlours, cobblers in the back; a bird-fancier in the first floor, three families on the second, starvation in the attics, Irishmen in the passage, a ‘musician’ in the front kitchen, a charwoman and five hungry children in the back one – filth everywhere – a gutter before the houses, and a drain behind – clothes drying, and slops emptying from the windows; ... men and women, in every variety of scanty and dirty apparel, lounging, scolding, drinking, smoking, squabbling, fighting, and swearing.”

Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz, 1839 on St Giles Rookery

An example of the typically poor accommodation of the time.

A scene of squalor in Victorian London.

Land values and the problems of urban squalor and poverty are issues with which Howard is well acquainted. As a young man he spends his spare time moving in various intellectual circles including nonconformist churchmen and other religious groups and reformers. The land question is a major source of discussion among these groups, including issues concerning land ownership, land nationalisation and land taxation. Howard also sees the various attempts being made by industrialists to set up healthy, well planned model communities for their employees.

In 1879 Howard married Elizabeth Ann Bills. They have three daughters and a son and, eventually, nine grandchildren.

Howard is interested in inventions and inventing, although he rarely makes any profit from his inventions, they are an important part of his life. Once an idea for a project takes shape he pursues the solution relentlessly even if there is no likelihood of any financial gain from his efforts. This drive and tenacity is what compels Howard in his pursuit to establish his vision of a model community.

George Bernard Shaw, a good friend of Howard’s, describes him as "one of those heroic simpletons who do big things whilst our prominent worldlings are explaining why they are Utopian and impossible. And of course it is they who will make money out of his work".

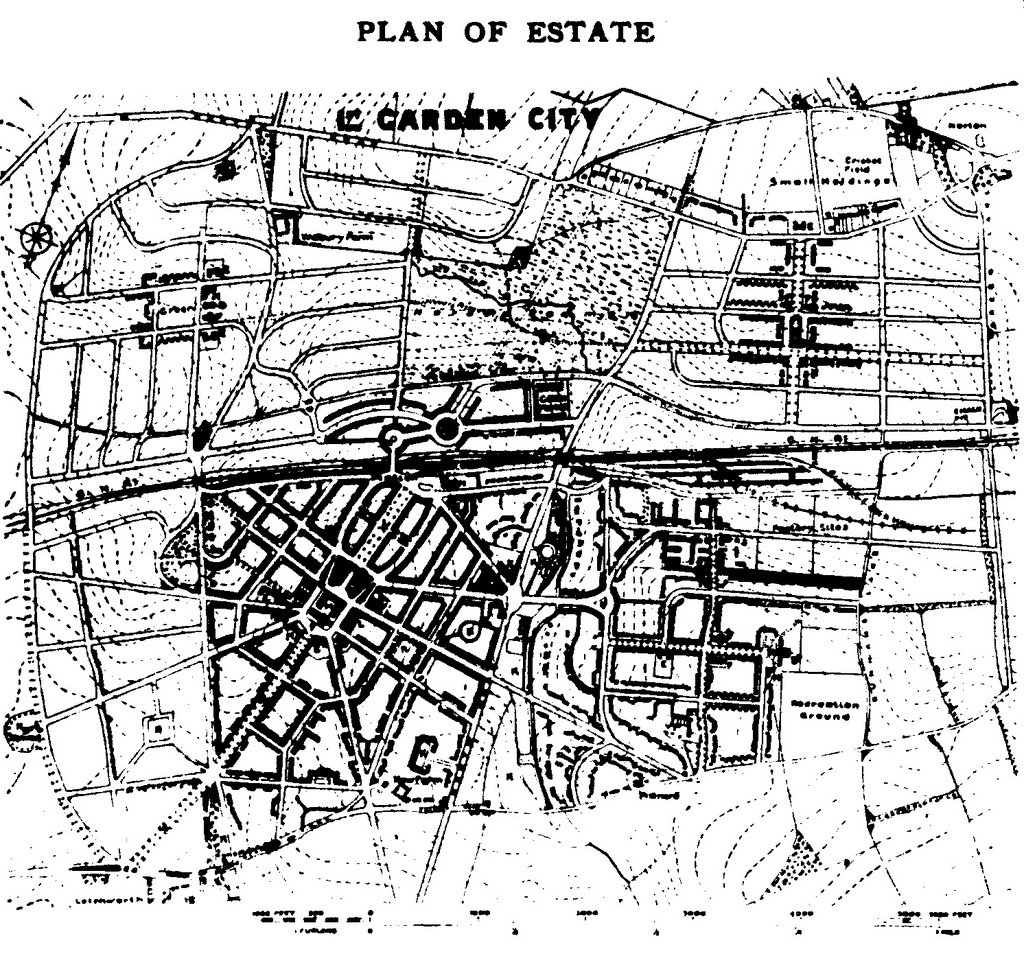

In 1899 Howard establishes The Garden Cities Association, which later becomes The Town and Country Planning Association and is still in existence. In 1902 The Garden City Pioneer Company is formed as plans get underway to create what Howard sees as an 'example city' to spark the interest of the nation and The Government. The Garden City Pioneer Company examines several sites and have virtually settled on Chartley Castle, near Stafford, when in April 1903 Herbert Warren, the Pioneer Company’s Solicitor, examines the Letchworth Hall estate, near Hitchin, Hertfordshire, which has recently become available. At just 1,014 acres the area is too small, however nearby land is acquired to give a total of 3,818 acres. First Garden City Ltd is registered in September 1903 and on October 9th, in a marquee south of Baldock Road, in the pouring rain, Earl Grey declares the estate open, appropriately, the location is now named Muddy Lane.

A competition is held for the layout plan which brings entries from prominent architects: William Richard Lethaby, and Halsey Ricardo; Geoffry Lucas and Sidney Cranfield; and Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin. In February 1904 the commission is given to Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin who have previoulsy designed the Model Village of New Earswick for the Rowntree Company. Their winning town plan is highly reminiscent of Christopher Wren's unrealised plan for rebuilding London after the great fire of 1666.

The site of Letchworth Garden City, the Letchworth Hall Estate, in the first decade of the town's inception.

A comparison view, showing the similarities, of Parker & Unwin's plan for Letchworth and Sir Christopher Wren's unrealised plan for London.

Born in Chesterfield to a bank manager father, Richard Barry Parker begins his training at T.C. Simmonds Atelier of Art in Derby and the studio of George Faukner Armitage in Altrincham. In 1891, he joins his father in Buxton and designs three large houses in the town for him. Parker’s early career is defined by his partnership, from 1896, with his close friend, half-cousin and brother-in-law, Raymond Unwin. Unwin would work on the more practical side of the commissions while Parker, being an accomplished artist, concentrates on the more creative aspects.

Born in Rotherham, Yorkshire, Raymond Unwin is raised in Oxford after his father sells his business and relocates there. After graduating from Magdalen College School, Oxford, he moves to Manchester, taking a job as a draftsman at a cotton mill. In May 1887, he undertakes a position as an apprentice engineer for Stavely Iron & Coal Company near Chesterfield. Here he designs industrial buildings and machinery and is also given the brief to construct housing for mine workers, albeit at minimum possible cost to by-law standards, giving him firsthand experience of the housing he would later strive to improve.

After forming a close friendship and formal partnership with Barry Parker, whose sister Unwin marries, they worked together on private commissions, on site planning and residential layouts.

After forming a close friendship and formal partnership with Barry Parker, whose sister Unwin marries, they worked together on private commissions, on site planning and residential layouts.

Parker and Unwin believe in the vernacular style of architecture and aim to popularise the Arts and Crafts approach to design. The Arts and Crafts movement slightly precedes Garden Cities emerging in the late 1880s; it is advocated by famed Socialist; William Morris and Writer; John Ruskin. The Arts and Crafts Movement revives traditional artistic craftsmanship with themes of simplicity, honesty, function, harmony, nature and social reform. The movement promotes moral and social health through quality of architecture and design executed by skilled creative workers and is a revolt against the poor quality of industrialised mass production. The  movement is not only concerned with the buildings themselves, which should be simple and in the Pre-Raphaelite style, but also with civic design. Whilst lecturing for the Socialist League, Morris describes his ideas regarding town planning most prominent of which are "decency of surroundings" which included: "Ample space, well built, clean, healthy housing, abundant garden space, preservation of natural landscape, pollution and litter free". Howard himself is a follower of Morris and quotes him in his book ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’. It is, therefore, a perfect union between Parker, Unwin and Howard.

movement is not only concerned with the buildings themselves, which should be simple and in the Pre-Raphaelite style, but also with civic design. Whilst lecturing for the Socialist League, Morris describes his ideas regarding town planning most prominent of which are "decency of surroundings" which included: "Ample space, well built, clean, healthy housing, abundant garden space, preservation of natural landscape, pollution and litter free". Howard himself is a follower of Morris and quotes him in his book ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’. It is, therefore, a perfect union between Parker, Unwin and Howard.

Barry Parker

Raymond Unwin

Tree-planting and landscaping are essential elements of the garden city image. Only one tree is felled in laying out the plan. Norton Common, a 63 acre parkland, is incorporated without any development. Trees and greenswards line the residential roads, hedges, shrubs and verges give the whole town a park-like appearance befitting the term ‘Garden City’

Above: Norton Common, Letchworth.

Opposite: Broadway, Letchworths grand, tree-lined boulevard.

The main axis running through the town is ‘Broadway’ a landscaped and tree lined boulevard. The residential areas adjacent to Broadway are artisan style housing and the lowest density of the town, whilst those nearer to industrial zones are of a higher density. Unwin defines the aesthetics and technical particulars to be adhered to in the ‘Letchworth Building Regulations’, a pioneer of its kind. He specifies: ‘Simple and straightforward building’ with ‘the use of good and harmonious materials’ and discourages ‘useless ornamentation’. Houses should be built in the arts and crafts style. Slate roofs are considered ugly and frowned upon, tiles are favoured over  slate, the local yellow brick is also seen to be inferior, red brick being the preferred building material. If brick is not left bare it should be pebble dashed or painted. However, larger and industrial buildings should be built in bare red brick as it gives the building additional gravitas.

slate, the local yellow brick is also seen to be inferior, red brick being the preferred building material. If brick is not left bare it should be pebble dashed or painted. However, larger and industrial buildings should be built in bare red brick as it gives the building additional gravitas.

Initially, the high standards for housing set by the planners results in a lack of working class abodes, this in turn stifles interest from industry contemplating relocation to Letchworth. In 1905, under the supervision of Parker and Unwin, the Cheap Cottages Exhibition launches in Letchworth. The exhibition remedies the problem of affordable housing by creating an abundance of homes fit for working class families, albeit at the cost of a perfectly uniform architectural scheme.

The guidelines set out by Parker and Unwin are rather open to interpretation, which is why many of the houses built for the cheap cottage exhibition are seen as poor attempts at mimicking the ‘Garden City style’. From the guidance document: "It should be remembered that a sunny aspect for the main rooms is almost as important as ample air space.... (there should be) no outbuildings at all; the w.c. or e.c. being under the main roof and entered from the porch or from a lobby outside. The promoters believe that by encouraging quite simple buildings, well built and suitably designed and grouped together, they will be helping to secure for the Garden City, a special charm and attractiveness by methods which experience shows are better calculated to ensure them than the lavish use of pointless ornament."

The exhibition attracts wide publicity and Helps to shape the Garden City in its fledging years;  this housing exhibition sees 131 unique homes built and demonstrates that sound housing can be provided at a cost of just £150 per dwelling. The exhibition attracts 60,000 people and its success prompts a second exhibition in 1907.

this housing exhibition sees 131 unique homes built and demonstrates that sound housing can be provided at a cost of just £150 per dwelling. The exhibition attracts 60,000 people and its success prompts a second exhibition in 1907.

The industrial heart of the town for many years is the Spirella corset company, opened in 1910 and housed in temporary sheds, the business soon moves to a spectacular Arts and Crafts inspired factory. Paradoxically the ‘quaint’ Arts and Crafts style is up-scaled to an industrial size; however, the factory is a triumph and is known by many as the ‘factory of beauty’ and ‘the factory in a garden’. Not only is the building an aesthetic success but Spirella is one of the largest employers in Letchworth in the early years. The company has a philanthropic approach to its workforce, providing health and education benefits as well as a thriving social life too. The company prides itself on the hygienic and health benefits of its product, especially the flexible patented Spirella stay, the quality of the product ensures the company’s success and it produces corsets and other undergarments until its closure in 1989.

As the town grows and road traffic increases a new type of junction is built. Designed by Parker and Unwin in their original 1904 town plan, the junction is called a ‘gyratory traffic flow system’ and is the first of its kind in the UK. The junction is now known as a roundabout, an essential part of the modern road system.

Despite the many commendations for Letchworth and its civic and social achievements, not only nationwide but also worldwide (The Garden City gains international acclaim, its most notorius fan being Vladimir Lenin who visits Letchworthin 1907), some are critical of the town and its inhabitants. An early resident offers a description of the ‘typical Garden citizen’, “who wore sandals, ate no meat, read William Morris and Tolstoy, and kept two tortoises which he polished periodically with the best Lucas oil”. George Orwell characterises the population as ‘every fruit juice drinker, nudist, sandal wearer, sex-maniac, Quaker, nature cure quack, pacifist and feminist in England’. Another detractor is John Betjeman who dedicates two poems to Letchworth− ‘Group Life: Letchworth’ and ‘Huxley Hall’ – both of which mock the community’s utopianism. The novelty of the town is such that Londoners, on their Sundays off, make special excursions by train to study Letchworth’s strange collection of smock-wearing Esperanto speakers and theosophists.

Critics of Letchworth are eager to condemn Parker and Unwin’s decision to favour an Arts and Crafts style. It is considered by many to be a style which, through rose tinted spectacles, attempts to replicate a style of twee, rustic and rural architecture which had never, in reality, existed. The style adopted by Parker and Unwin, in the opinion of their critics, is akin to that of the 18th and 19th century’s landed gentry, who would adorn their estates with follies in the form of idyllic and twee rural villages and hamlets. It is ironic that this method of design, which harks back to a bygone era, is popularised by its use at Letchworth to the extent that it has a major influence on the future of British architecture.

The Spirella Factory, Letchworth.

An example of a home promoted in the Letchworth Cheap Cottage Exhibtion of 1905

Examples of Letchworth Garden City's "idyllic and twee" take on Arts & Crafts architecture.

Howard himself is, by some, considered to be wholly unoriginal since the notion of the garden city is derivative of earlier concepts. Johann Jakob Moll’s 'Plan for a City of Hundred Thousand Souls' published in 1801 and James Silk Buckingham’s conceptual city of Victoria, from his 1849 work 'National Evils and Practical Remedies: With the Plan of a Model Town', precede Howard’s work. In addition, Howard is greatly influenced by a popular work of utopian science fiction: ‘Looking Backward: 2000–1887’ by the author Edward Bellamy. Bellamy describes a socialist utopia which replaces the bleak reality of the 19th century, a notion which Howard would relish. Indeed, Howard is so taken with the novel that he purchases a number of copies to distribute among his friends. It is clear that Howard is somewhat imitative in his concept of the Garden City, however, the fact that he executes his plan, bringing it in to reality, is his greatest and most celebrated achievement.

In 1919, following the success of Letchworth Garden City, Ebenezer Howard purchases land in Hertfordshire which is to be the site of his next venture, it is named Welwyn Garden City. Louis de Soissons is appointed Town Planner and Architect, Welwyn is the young partnerships first commission. The Louis de Soissons partnership remains involved with Welwyn for a further 60 years and flourishes in to, what is now, one of the foremost architectural partnerships in the UK. Also recruited to spearhead the Welwyn venture is Frederic Osborn who is appointed Secretary of Welwyn Garden City Ltd. Osborn first encounters Ebenezer Howard and the world of Garden Cities after obtaining the post of Secretary to the Howard Cottage Society. At the time of his appointment Osborn knows practically nothing of Letchworth or the history of its incarnation. However, having moved from the confines of London to idyllic Letchworth, Osborn becomes a  devotee of the Garden City movement, embracing the cause which, as Howard's most dedicated disciple and propagandist, is to dominate the rest of his life.

devotee of the Garden City movement, embracing the cause which, as Howard's most dedicated disciple and propagandist, is to dominate the rest of his life.

De Soissons designs a beaux-arts layout planned around two boulevards. The main boulevards are Parkway, a grand tree lined street and The Square, running north to south alongside the Great Northern Railway which bisects the town. As with Letchworth, the town is zoned in to commercial, industrial and residential areas. The residential architecture has moved on from the vernacular Arts and Crafts style favoured by Parker and Unwin, De Soissons favours a genteel Neo Georgian style. However, the landscaped areas within the town, key to the healthy living values of the Garden City movement, are perfectly in step with the precedent set by Letchworth. The most prominent of these landscaped areas is the parkland which runs alongside the mile long Parkway.

Parkway, one of the main boulevards of Welwyn Garden City.

Despite Welwyn’s many attractive features, growth is initially slow and by 1926 just 1,800 houses have been built. Critically, industry is set up in Welwyn, this includes the Shredded Wheat Factory, Roche Products and Murphy Radio. The population grows in response and by 1938 the population numbers 13,500.

Although not as original or influential as Letchworth, Welwyn becomes an iconic town attracting much interest. Japanese town planners visiting the Garden City are so impressed that they name a new development near Tokyo ‘Welwyn Garden Village’.

Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities are not only highly successful as towns in their own right, but have a colossal impact on housing developments nationwide in the early decades of the twentieth century. Despite Howard’s hopes for a land of Garden Cities adhering to his guidelines, developers take inspiration from various aspects of his creations and use them to enhance their own. Dozens of Garden Suburbs, Garden Villages and various other new communities use the vernacular Arts and Crafts style of architecture alongside his low density, landscaped and tree-lined civic design. The emphasis on the beauty of nature and the benefits to resident’s health and wellbeing are valued as they had not been before.

Furthermore, the aesthetics of Parker and Unwin’s approach to architecture, landscaping and civic planning have a profound effect on the appearance of British towns and suburbs. The appeal of their simple yet elegant designs capture the imagination of generations of architects and elements of their influence can be seen in almost every residential development of the past century.

Henrietta Barnett and Samuel Augustus Barnett

The Next Chapter...

In the wake of World War Two it is decided by the British government that overspill towns are required to ease overcrowding in cities. Inspired by the precedent of Garden Cities a number of countrywide projects are undertaken. In 1967 parliament announces a plan to create a brand new city in Buckinghamshire fit for 250,000 inhabitants, it is named Milton Keynes after a tiny village which exists within the 100 hectare expanse of the proposed metropolis. Milton Keynes is described by its audacious young architect, Derek Walker, as ‘the city in a forest’ and is a bold combination of rural idyll and American inspired modernity, built around a grid system of highways.

Further reading...

Garden Cities

Sarah Rutherford

Foundations in Urban Planning - Ebenezer Howard: Garden Cities of To-Morrow & the Garden City Movement Up-To-Date

Ebenezer Howard, Ewart Culpin, Thomas C Myers Jr

London's Metroland

Alan A. Jackson

British Architectural Styles: An Easy Reference Guide

Trevor Yorke

© 2021, D A Phipps, All Rights Reserved